a new fine art project by matthew rolston

5 MIN READ

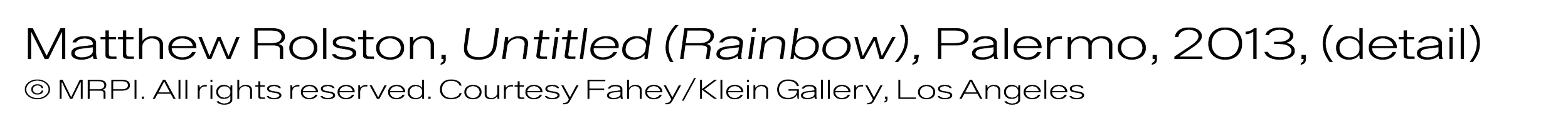

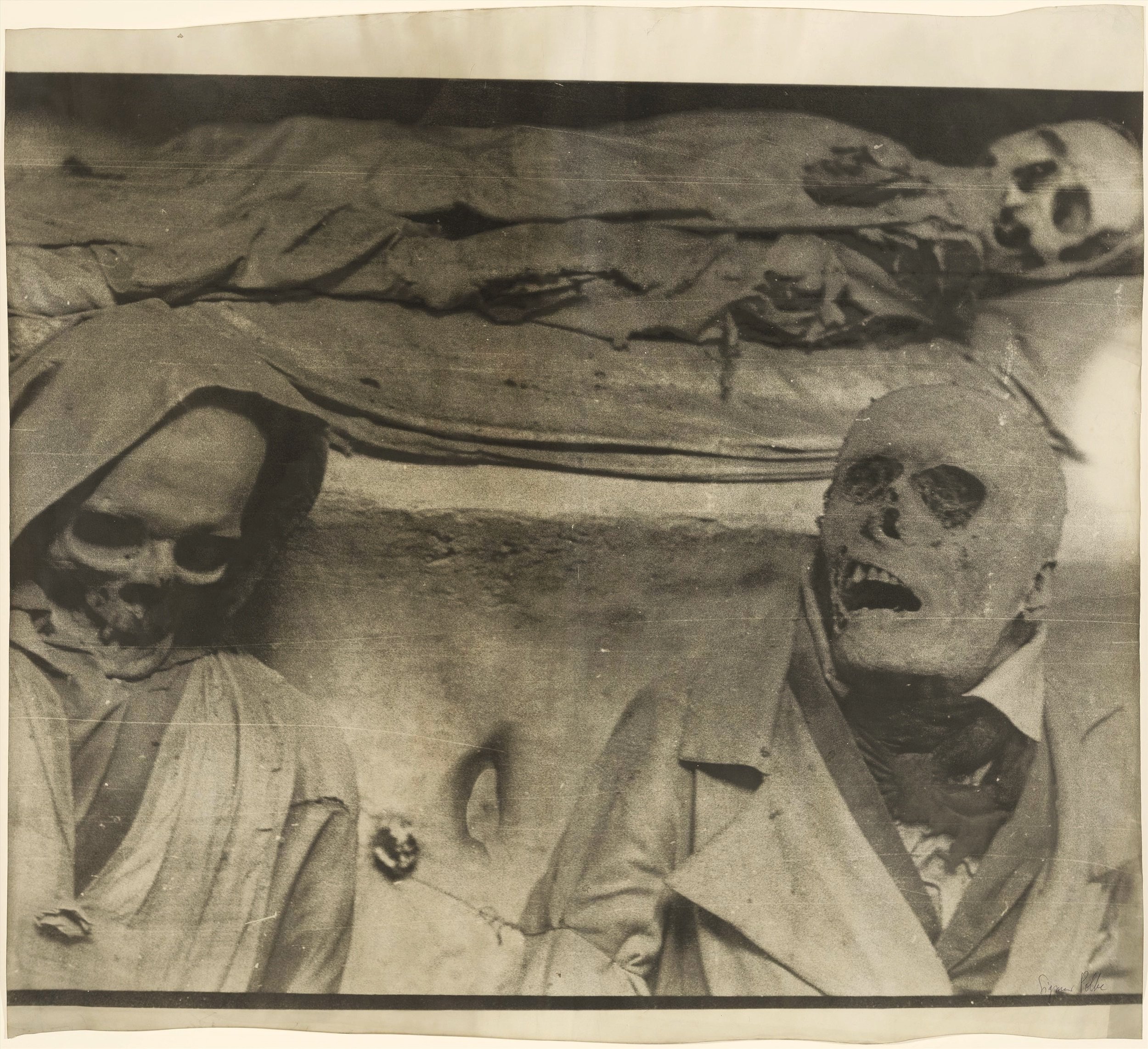

DRAPED IN SILK, VELVET, OR SACKCLOTH, and propped up with wires or crudely hooked into niches, the remains of over 8,000 mummified corpses adorn the lime-covered walls, shelves and variously scattered vitrines of the Capuchin Catacombs in Palermo, Sicily.

For nearly five centuries, from the 1500s through to the early 20th century, Palermo’s elite preserved themselves as either a marker of their piety or a symbol of their enduring vanity. Now transformed by time into slowly decaying relics of humanity barely held together, Matthew Rolston’s depiction — Vanitas: The Palermo Portraits — is an immersion into this world of death after death, comprising a portrait series and associated publication that bring forth an interwoven meditation on beauty, mortality and art through a uniquely photographic lens.

Coming from a celebrated background in Hollywood portraiture and entertainment, Matthew Rolston has since spent nearly two decades of his career focusing on creating conceptual photographic art series that push on the edges of portrait photography. His recent bodies of work include large scale images of ventriloquist dummies in his Talking Heads series, followed by his Art People series documenting the elaborately costumed and theatrically made-up participants of the Laguna Beach tableaux vivants show known as Pageant of the Masters. Rolston’s Vanitas works are perhaps his most challenging and ambitious yet, and which pull at themes ever-present across his past work.

Produced in 2013, Vanitas was made over a one-week period following months of extensive preparation and planning. The project involved a six-person team using specialized lighting and camera equipment to document well over 50 mummified remains in the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, Sicily. Working throughout the night, Rolston shot the catacomb mummies as he would a living subject but utilized an unconventional lighting technique to achieve a vivid, painterly coloration. Through a proprietary process Rolston refers to as “expressionistic lighting”, he combined theatrical colored gels across three different wavelengths to produce a unique effect. The resulting hues of shadowed and shaded greens, golds, yellows and blues reanimate these lifeless figures, from their bones to their tattered clothing, all set against an intense bluish-cyan background tone indicative of Catholic iconography.

Rolston’s Vanitas images, on one hand, serve to counter the output of his early career in celebrity glamour portraiture, where notions of aging, death, or even the passage of time itself were either absent or actively negated.

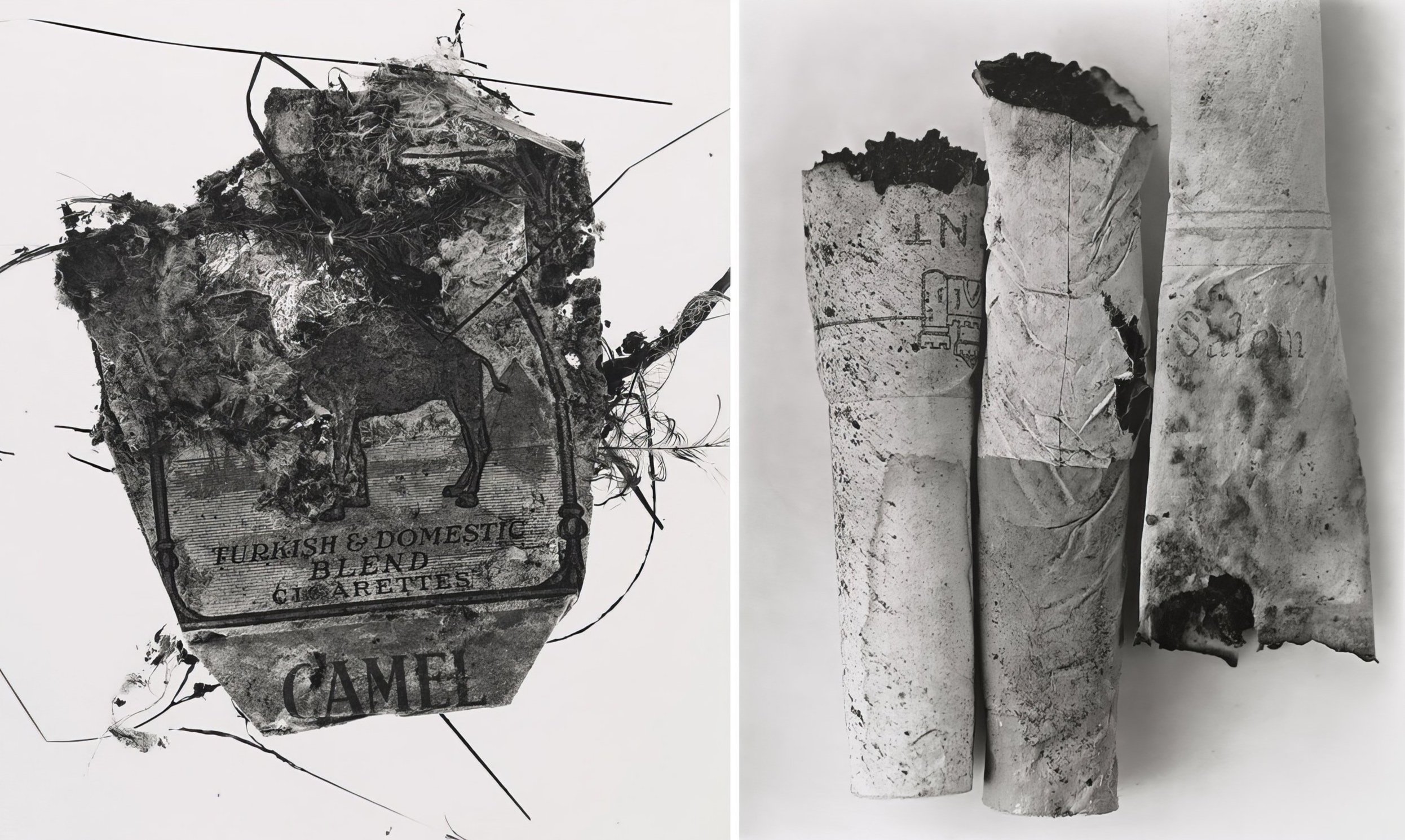

Rolston’s focus on blemish and not polish is formally rooted in the same spirit of photographer Irving Penn’s 1970s “detritus” series, wherein Penn took discarded items like cigarette butts, sidewalk gum, and crushed paper to form them into elegant, arresting compositions. Rolston’s large-scale portraits share in Penn’s gesture; here, human remains are given a lapidary, jewel-like quality that tease between the serene and the grotesque. A color palette reflective of stained-glass cathedral windows becomes realized in the direct visage of human decomposition, literally rendering bare the mortification of the flesh through its putrefaction.

In order to understand our world and its many conflicts, human beings separate themselves through discrete spiritual belief systems, with sometimes highly contested boundaries. Vanitas seeks to transcend the boundaries that divide us, which may limit our perceptions of the world, of the relationship between the living and the dead, and of the subjectivity of our relationship to time. The work attempts to demonstrate that the human experience exists in a long, fragile yet miraculous, borderless and unified continuity.

A formal cognitive dissonance through color and content matches Rolston’s conceptual intent, which is to postulate that the concept of death is impossible for the human mind to comprehend without some relationship to the world of the living. Most specifically, Rolston references photographer Richard Avedon’s emotionally intimate portrait series of his father Jacob, confronting mortality in the final years of his life, as well as his images of aging Hollywood directors, such as the unsparing 1972 portrait of John Ford made one year before the legendary filmmaker’s death. Capturing both vulnerability and physical decline, Rolston, like Avedon, notes in his images how the idea of death can only be experienced by those in the world of the living. In this same way, concepts of life and death in Vanitas are irrevocably intertwined.

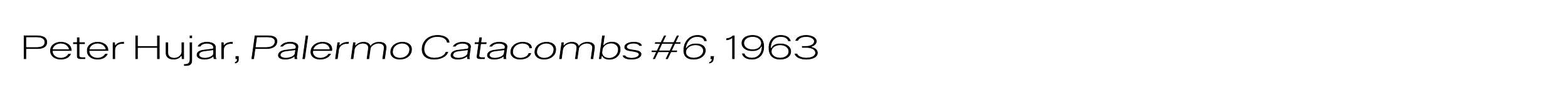

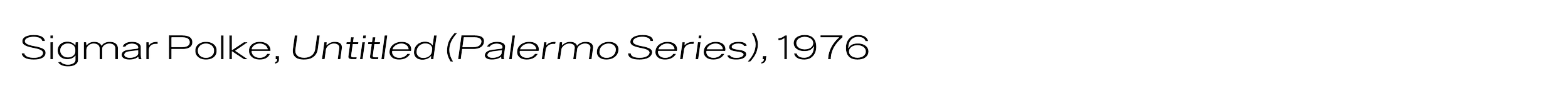

Susan Sontag, commenting on artist Peter Hujar’s 1963 body of work in the Capuchin Catacombs, notes how photography as a practice, “converts the whole world into a cemetery. Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also — wittingly or unwittingly — the recording-angels of death. The photograph-as-photograph shows death. More than that, it shows the sex-appeal of death.” Rolston, as a student of the major portraiture schools of the 20th century, takes much inspiration from fellow photographers as well as painters who have ventured into the catacombs that have, outside of Hujar, also included Richard Avedon, Otto Dix, Sigmar Polke and others.

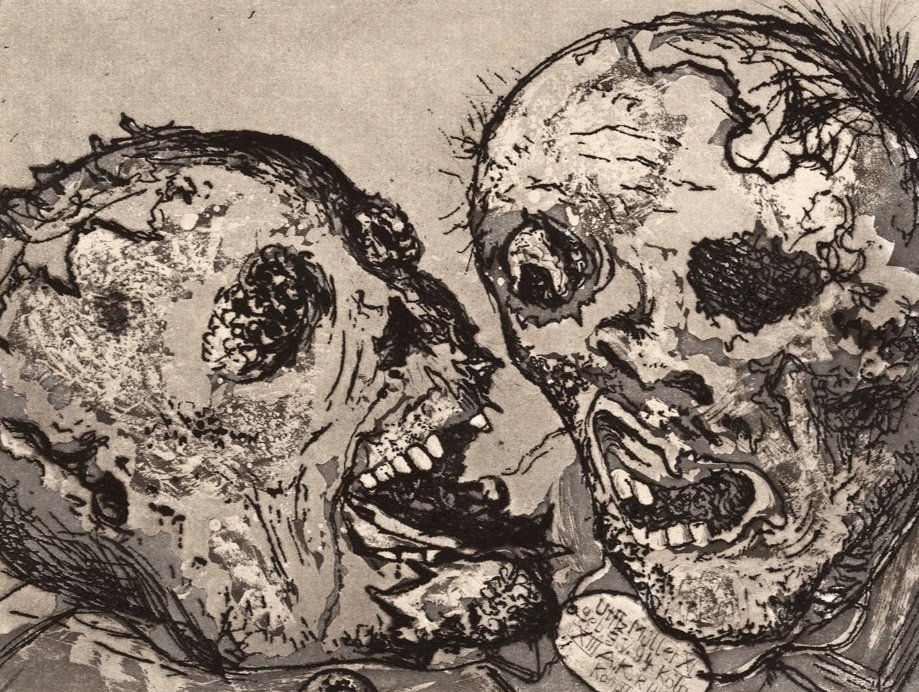

In Vanitas, Rolston particularly references Dix’s 1924 series From the Catacombs in Palermo, produced in between his The Trench and The War bodies of work. Made during a period of intense focus on loss and death in the wake of the First World War, Dix’s watercolor of a Capuchin mummy with its jaw held open, lifeless, could symbolize the decay of any hope of redemption in the hereafter.

Rolston’s works similarly focus intensely on the perceived facial expressions of these mummies, from gaping jaws seemingly screaming in silence, to threadbare smiles with what little teeth may still be left. Though these people no longer speak, feel, or think, it is nearly impossible for the viewer to engage with them without projecting a certain humanity onto the mummified body, reflecting the impossibility of conjuring death in the living mind.

Cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker famously wrote, “Man cannot endure his own littleness unless he can translate it into meaningfulness on the largest possible level.” In these images, Rolston makes a direct encounter with humanity’s anxiety of death, interrogating an anthropological need to construct answers for what lies beyond the human timeline. Noted historian, professor and writer Yuval Noah Harari comments on the human awareness of death as foundational to some of the most important structures of the civilized world. In his book Sapiens, Harari asks, “Try to imagine Islam, Christianity or the ancient Egyptian religion in a world without death. These creeds taught people that they must come to terms with death and pin their hopes on life after death, rather than seek to overcome death and live forever here on earth. The best minds were busy giving meaning to death, not trying to escape it.”

In Vanitas, Rolston leaves unanswered whether those he has photographed have found, through the mummification process, salvation in the afterlife, or whether that afterlife simply lives on vicariously through the viewer. What he firmly establishes, however, is a symmetry between photography and the human desire for immortality, something that connects with his past work constructing timeless vignettes of Hollywood icons. With this series, Rolston challenges the limits of death and decomposition to find elegance within the human form, probing to assert that beauty may yet be found even within these crumbling strands of bone and flesh.